…Capoeira de Angola é devagar!

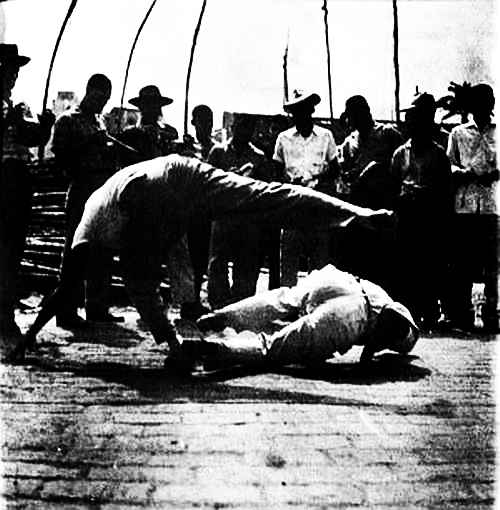

The aim of this post is to highlight an important, but often overseen aspect of Capoeira Angola. I myself do oversee it far too often and while I was thinking about it the idea came up to make a blogpost out of it. The aspect of Capoeira Angola I want to point at this time is “playing slowly”.

The speed of your game

Most people do know that Capoeira Angola is generally played in a slower pace than Capoeira Regional. In fact, some people think that Capoeira Angola is just the slower version of Capoeira Regional. I wont go into that one, because most of the fans and players of Capoeira know that it’s not right anyway. Some people also know that Capoeira Angola games are highly variable in terms of speed. A game can switch from slow to fast to slow in less than ten seconds. That Capoeira Angola is always slow is a common misunderstanding which usually leads to some unpleasant surprises. But, and that’s what this post is about, it is still an important attribute.

Why?

There is many different reasons why Capoeira Angola is played in a slow base rhythm. I will just count the most common (and obvious) of these:

- Endurance: As a typical game in Capoeira Angola goes into the minutes and can easily go on for more than 10 minutes a high pace is not recommendable. In comparison, games in some Regional rodas are incredibly short, sometimes it’s a matter of a few seconds until you get bought out. This short timespan forces you to get into a game as fast as possible. If a game in a Regional roda would take 10 minutes retaining its speed, most people would drop unconscious 😉

- Safety: A Roda is not always a safe place. In Capoeira Angola your space is petty limited. It is almost impossible to be not enangered when a person in a two-meter-diameter-roda does make a fast kick. For the safety of you and your partner it is recommandable to slow down the game, even if it gets faster in between. And even if you dont care much about the other person you are playing with the rule applies “what goes around, comes around”. Play fast and you will get a fast response. Thus, it is sometimes just smarter to play at a slower pace.

- Aesthetics: Players of Capoeira do regularly state that Capoeira Angola is much more expressive and playful than Regional or Contemporean Capoeira. This would not be possible in a high speed game. The higher the speed of the game the more people (especially beginners and not-so-advanced players) concentrate on not getting hit, hitting the other person and maybe even performing a good game. And the first things dropped would be the playfulness and the individual expressions you can do in a roda. Thus, a too fast game which keeps on staying too fast is often seen as an “ugly game” Angola roda, more because of the lack of grace and mandinga than because of the speed.

- Precision: Here I will quote my first teacher. During training he liked to tell us “I have you rather doing the movements 3 times right than 30 times wrong”. He used to say this when the students sped up in training and started being sloppy with the movements. This does easily apply to a game. The faster a game is the less time you have for precise movements, the sloppier you get. That can lead to accidents involving you and/or your partner. Or, it can just lead to the movements looking short, uncomplete, ugly. Having time during the game does give you the chance to do your movements right, precise and with grace.

- Health: It is indeed healthier to play slow than to play a fast paced game. This does count for the individual game as well as on the long term. Why? The faster the game the higher is the danger that you dont listen exactly what your body tells you. An Au you might go into might be started wrong and risking your back or your limbs. In a fast game the chance to correct this fault is lower than in a slow game. For example: in an Angola game which was a tad too fast a friend of mine did almost cripple himself doing an Au malandro (I think some people call it an Au batido). He had so much speed that his upper arm moved forwards while his hand was planted and his upper body falling backwards – to make it short: for a split of a second his elbow was on the wrong side of the arm… In terms of longterm effects of fast playing wearing off of knees and wrists is one of the most prominent Capoeira illnesses. Jumps and rapid stressing these vulnerable body parts do have a bad effect in long term (although: I am talking here out of a mixture of experience and pure logics. I have no statistical or medical data for this. But it would be interesting if somebody would investigate this!)

Counting in the music

An obvious reason for playing slow in the Roda de Angola is that it otherwise wouldnt fit to the music. Most people know that a game is not an exact representation of the Berimbau’s rhythm played in the Roda (meaning, the steps and kicks dont come in the same rhythm as the berimbau is being beaten). But there is a linkage between the music and speed of the game. The players have to follow the music in this case. Thus, when they speed up and dont turn back to a slow pace while the music is slow the whole time, they will most possibly be called to the Pé do Berimbau and reminded of playing slowly. Or they will hear the song “Devagar, Devagar”. Here is the lyrics of this song (not exactly what I learned but nicely written down by Mathew Brigham (Espaguete) in his very good “Capoeira Song Compendium“)

Devagar, devagar Slowly, Slowly

Devagar, devagarinho Slowly, very slowly

Refrain: Devagar, devagar Slowly, slowly

Cuidado com o seu pezinho Be careful with your foot

Capoeira de angola é devagar Capoeira Angola is played slowly

Esse jogo é devagar This game is slowly

Eu falei devagar, devagarinho I said slowly, very slowly

Esse jogo bonito é devagar This pretty game is played slowly

Falei devagar, falei devagar I said slowly, very slowly

This song is sung to a slow rhythm, which makes it almost impossible to be ignored by the players. And if they do so, it usually results in being reminded specifically/personally, or just asked to stop that game. So why does the music then have to be so slowly? Well, first of all, it’s a question of taste. Capoeira Angola music is slow to medium paced, with a lot of different nuances and a rich sound. This does come because a) the presence of 7 instruments incl. 3 differently pitched berimbaus gives a very rich acustical caleidoscope and b) the low speed of playing allows for wonderful variations (especially of the Berimbau Viola). I know, for a lot of modernist Capoeiristas it is too slow, but people wont understand that keeping a rich sound and keeping a slow pace is actually much harder than just beating the crap out of your berimbaus and drums. I speak out of experience that keeping the rhythm slow is harder than just playing a fast rhythm. And, as in Capoeira Angola slower games are preferred, the Bateria does control this by controlling the speed of the music.

How to achieve a slow game

Now, this is the most complicated part of this post. Because, to be sincere, I dont know a perfect recipe to keep your speed slow. I too get faster while playing and I guess I am not alone in this. I guess it is the same as with drumming. The natural tendency seems to be that you want to get faster. You might start with a slow rhythm (in playing or in music), but if you dont take care of it you will get faster. I want to point out that it is not bad to become faster. The player just has to know when to get back to “normal” speed again and when being fast helps, and especially when it doesnt.

Thus, the simple (and admittedly not very helpful) answer is: focus. Concentrate on te speed of your movements. Not too slow, but also not hastily. Before you can do that you have to get used to play in the Roda of course, and get secure. Thus it helps when you are not a pure beginner in Capoeira Angola. This doesnt mean that if you are a beginner you are free to play as fast as you wish. You can immediately start concentrating on playing slowly. But if you lose your focus on playing slow, dont worry, try harder next time. As a beginner you usually just dont have the peace of mind to play slowly yet. You get nervous, you get hasty. Being calm and relaxed is key here.

It also helps to be a bit mature. When you want to impress, show off, make fun of a your partner and have similar immature ideas about playing you usually dont go for the slow movements. But maturity is something you cannot train. That comes by itself, hopefully.

In the 90’s mestre Cobra Mansa came to the US and founded the International Capoeira Angola Foundation (ICAF in English, FICA in Portuguese) in the year 1995 together with Mestre Valmir and Mestre Jurandir. FICA is now one of the most famous representatives of Capoeira Angola in the world, having opened up school worldwide. Especially in the US, but also in Mozambique, Russia, France, Hawaii, Costa Rica and, of course, Bahia amongst others. The size of this organization has led to some critics as far as I have heard. I couldnt get much information out of them, but it looks as if people are afraid of a monopolization of the Capoeira Angola in similar ways as it happened in Capoeira Regional, where Senzala, ABADA and Co. dominate the “market”. there is little one can argue against that kind of fear, but one can surely say that FICA doesnt see itself as unique or special. As far as I have had the pleasure to meet people from FICA they seemed not to be discriminating between them and “other” angoleiros and I have not heard of one occasion where it was different. So for me there is no reason to doubt on FICA’s positive impact on Capoeira Angola.

In the 90’s mestre Cobra Mansa came to the US and founded the International Capoeira Angola Foundation (ICAF in English, FICA in Portuguese) in the year 1995 together with Mestre Valmir and Mestre Jurandir. FICA is now one of the most famous representatives of Capoeira Angola in the world, having opened up school worldwide. Especially in the US, but also in Mozambique, Russia, France, Hawaii, Costa Rica and, of course, Bahia amongst others. The size of this organization has led to some critics as far as I have heard. I couldnt get much information out of them, but it looks as if people are afraid of a monopolization of the Capoeira Angola in similar ways as it happened in Capoeira Regional, where Senzala, ABADA and Co. dominate the “market”. there is little one can argue against that kind of fear, but one can surely say that FICA doesnt see itself as unique or special. As far as I have had the pleasure to meet people from FICA they seemed not to be discriminating between them and “other” angoleiros and I have not heard of one occasion where it was different. So for me there is no reason to doubt on FICA’s positive impact on Capoeira Angola.